Gone MAD: How Golden Dome Threatens the Logic of Nuclear Deterrence

For the first time in decades, America is attempting to vastly improve its defenses against nuclear attack—and this might be the most dangerous thing it can do. Golden Dome promises to provide layered, potentially impenetrable defenses against air and missile attacks against the homeland, and to many, this initiative might seem like a logical and reasonable course of action. However, the development of Golden Dome would make fundamental and irreversible changes to the security architecture of the international order, and these changes require careful consideration.

In January 2025, President Trump signed an executive order titled Iron Dome For America, which has since been renamed Golden Dome for America. This order begins actions that will presumably culminate in the development of a new integrated air and missile defense system for the American homeland. The logic behind Golden Dome also offers insight into the strategic vision of the Trump Administration. While seemingly defensive in nature, Golden Dome represents the conviction that continuous competition between nuclear powers is not an enduring feature of international relations, but rather a game that can be won. By this logic, Golden Dome will upset the nuclear deterrence framework of mutually assured destruction (MAD), under which the world has enjoyed decades of nuclear peace. This article provides a brief introduction to MAD and its historical context, examines how Golden Dome will disrupt MAD, and briefly discusses what this disruption may mean for the future of strategic competition.

Understanding MAD

Mutually assured destruction or MAD refers to the conditions of competition between nuclear states where any nuclear attack would lead to the destruction of both states and their respective societies. In these conditions, there is no advantage gained from being first to strike an adversary, and there is no incentive to disarm.

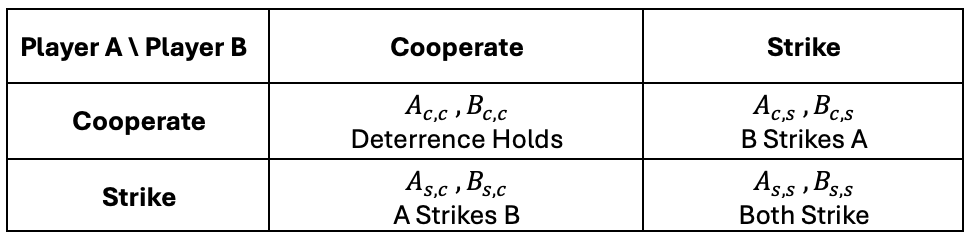

Throughout the Cold War, game theory was often used to understand the framework of nuclear weapon employment decisions, as championed by preeminent 20th century polymath and War quant John Von Neuman. In a simple two-player context, the game is simple: each player has the decision to cooperate or strike. Let us call these players A and B. We can then represent the payoffs of each player given the other player's decision in matrix form, where the players’ utility is shown for each decision combination.

We can then represent MAD in this form, as shown in the figure below. The utility values here are arbitrary representations of the negative consequences of an attack by either party, since any strike will result in retaliation from a second-strike capable force. The dominant choice – or Nash Equilibrium – for each player here is clearly cooperation.

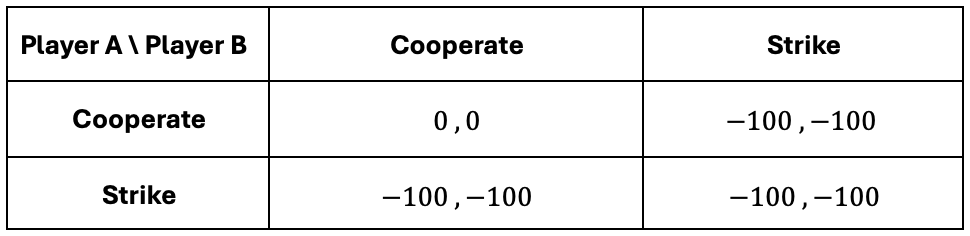

Early in the Cold War, the conditions for MAD did not exist. During his administration, President Eisenhower felt that the United States held a nuclear advantage over the Soviet Union, while the Soviet Union maintained an advantage in conventional mass. For the limited time that the United States possessed a nuclear advantage, the game of nuclear competition was unstable, since the United States possessed a legitimate incentive to strike first to avoid fighting a conventional conflict.

A game theory representation of a situation in which one party possesses a nuclear capability advantage can be seen in the payoff matrix below. Player A has a large incentive to strike first, as he can hurt his enemy without much fear of counterattack by potentially knocking out his adversary’s entire strike capability in the first action. Player B has more to lose by striking first, but still may have incentives to do so. For example, Player B can inflict damage on Player A in a first strike, but without the ability to destroy Player A’s ability to counterattack, Player B will still suffer disproportionately in retaliatory strikes, though less severely than if Player A had struck first. This represents a very unstable situation for both players. Player A has clear incentives to strike first, and Player B also has clear incentives to strike first if he believes Player A’s strike is inevitable. Such an unstable nuclear paradigm was arguably the case for much of the early Cold War years in some form or another.

Strategic Defense or Security Breakdown?

Building the Golden Dome means MAD is over. The executive order specifically mentions layered defense against countervalue attacks – where countervalue attacks refers to attacking targets of value to the adversary’s society, such as population centers, economic hubs, and critical infrastructure rather than targets of direct military significance.

Defense against countervalue attacks is not entirely new for the United States. However, since the end of the Cold War, American nuclear posture has been focused on rogue nuclear states like North Korea. The Golden Dome order envisions going beyond defending against threats from rogue states, and focuses instead on defending against countervalue strikes from America’s most capable nuclear adversaries. While North Korea has been improving its strike technology, defending against North Korean nuclear attacks does not compare in scale or complexity to defending against strikes by Russia and China.

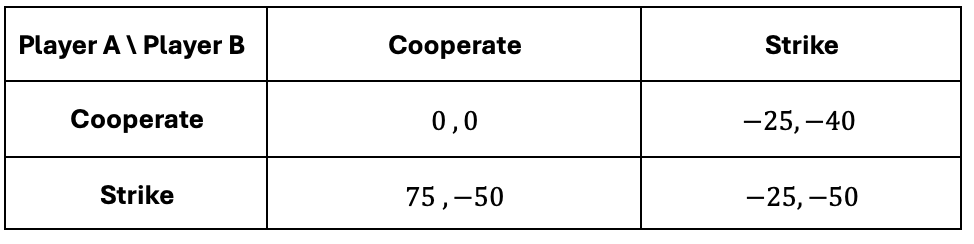

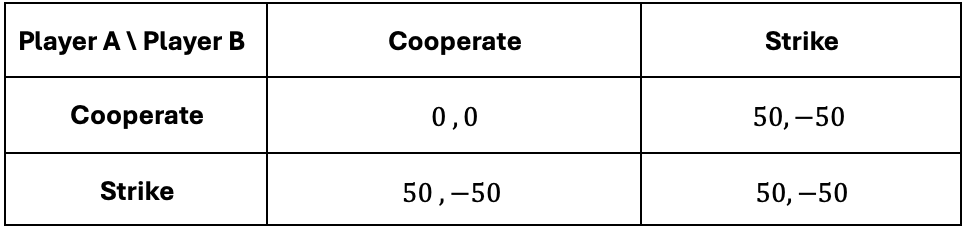

If successfully implemented, Golden Dome would remove the condition of mutual vulnerability and alter the decision-making framework for all belligerents. When one side becomes invulnerable, the game changes entirely. Consider an alteration to our earlier payoff matrices. In this case, Player A is now invulnerable to strikes and counterattacks by Player B.

In this example, reaching invulnerability is clearly in the interest of both players. However, reaching invulnerability does not happen without advance warning, and the signal that a country is pursuing significant defensive upgrades invites other actors to react in the meantime. In the case of Golden Dome, America’s adversaries may perceive that the United States is trying to gain an advantage in a nuclear conflict, and this fact alters the decision-making calculus for all players and introduces new instability in nuclear competition. For example, if Russia or China perceive that the altered nuclear paradigm created by Golden Dome would be to their long-term disadvantage, they may be incentivized to strike preemptively before the Golden Dome is in place. Additionally, should Golden Dome be successfully implemented, actors could perceive a nuclear strike as less escalatory if there is reason to believe the attack would be intercepted, making this form of nuclear brinksmanship a part of crisis escalation (consider the missile attacks of Iran on Israel as a non-nuclear parallel).

If another nuclear power develops its own countervalue defense system, nuclear dynamics could become even more dangerous. Other nations could see a massive build-up in nuclear weapons as the only way to offset increasingly capable nuclear defense systems. Likewise, in a world in which every nuclear power must develop their own countervalue defense systems, the decision space may become hugely complex as every player compares their relative offensive and defensive advantages to every other player. While some potential outcomes are speculative, changes in the dynamics of nuclear competition will greatly increase the chances of a new nuclear arms race among great-powers – and this may have already begun with China’s nuclear modernization.

Extended Deterrence and Non-Proliferation

MAD didn’t just deter adversaries – it also reassured allies under the concept of extended deterrence. Under MAD, Boston and San Francisco are just as vulnerable to nuclear attack as Berlin and Tokyo. Under such conditions, allies of nuclear powers could be reasonably assured that their nuclear ally would not drag them into a nuclear conflict in which the non-nuclear state absorbs the strikes. This is of course because the nuclear state is not able to control or defend against any attacks either on its own homeland or the homeland of its allies.

Under these conditions, non-proliferation arguments make sense, since non-nuclear states can fall into the MAD architecture without arming themselves. However, with Golden Dome protecting the American homeland, the United States could potentially climb the nuclear escalation ladder with few consequences for its own safety, leaving adversaries like Russia or China with no credible option but to strike America’s more vulnerable allies instead. In this world, non-nuclear states could feel obligated to begin developing their own nuclear weapon programs as a deterrent.

Imagining Victory in Competition

Despite the disruption and risk possible due to the development of Golden Dome, there are potential upsides and opportunities. MAD has always had its critics. Some argued that MAD – and adjacent policies such as détente – implicitly accepted bipolar great power competition and its associated spheres of influence as enduring features of international relations as the permanent status quo.1

It took some imagination and disruption to challenge Cold War logic and envision what victory under a different paradigm might look like. President Ronald Reagan could be credited with having such a vision. Reagan rejected détente, amped up pressure on the Soviet Union, and departed from diplomatic norms that created Cold War stability. Examples of this strategy included the Strategic Defense Initiative, Reagan’s plan to build a capability similar to Golden Dome. Had it been successful, this missile defense capability would have disrupted the nuclear deterrence framework as described above, but the technology underpinning the initiative did not materialize.

While the stability of the existing order secured by MAD may be under threat, President Trump and his strategy advisors would not take this step unless they believed there was an inherent advantage for America and its interests. Indeed, select criticism of President Biden’s approach to strategic competition with China observed that the administration simply sought to compete rather than define or achieve victory. An ambitious plan like Golden Dome could be seen as an attempt to move beyond status quo competition and towards victory.

One way to understand this logic is to envision Golden Dome as a tool to prevent vertical escalation in a future regional war. Consider a scenario in which China invades Taiwan. China could threaten nuclear strikes against the US homeland to deter intervention. Under MAD, this creates a credible threat of mutual destruction and may successfully deter US involvement, especially if the sovereignty of Taiwan is perceived as being secondary to the consequences of nuclear war.

Similar logic was apparent in the Biden Administration’s cautious response to Russian nuclear threats in the Ukraine conflict. President Biden showed real concern over the risk of nuclear escalation, and this often translated into a slow, carefully calibrated, and risk-averse approach to Ukrainian aid.

In contrast, a functioning Golden Dome defense may embolden the United States to be more assertive in situations involving risk of nuclear escalation. Reduced homeland vulnerability could give US leaders more freedom of action abroad, particularly when pursuing national objectives in confrontations with nuclear-armed powers. Of course, this shift would create new risks for US allies, who may remain vulnerable to countervalue attacks, but the overall logic of assertiveness remains and aligns with an America-first approach.

Towards a New Nuclear Future

Golden Dome may mark the end of MAD, but its implications for global security are far from certain. The creation of Golden Dome demonstrates the United States’ desire to push out of a stable equilibrium to a position of advantage. Other states will certainly respond. Indeed, China is already embarking on overhauls to its nuclear programs. Perhaps a new equilibrium will emerge, but for now, the risk of miscalculation has increased as global nuclear powers transition from mutual vulnerability to asymmetric capability.

The views and opinions expressed on War Quants are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or any other agency or organization.

The argument was made by John Lewis Gaddis that Reagan saw beyond the status quo of détente and other Cold War norms to see scenarios of US victory.

This is a really interesting piece. Reminds me of Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press' The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence arguing that the rapid change in technology will be the end of MAD.

scorpions in a bottle