The First Offset: Cold War Lessons for Renewed Great Power Competition

American Grand Strategy and Eisenhower’s New Look

The United States has entered a new era of great power competition, often compared to the Cold War. As policymakers grapple with military strategy today, revisiting past efforts to counter strategic competitors may prove instructive. One early attempt in this new era of competition was the Third Offset strategy, which drew its name from Cold War precedents — the First and Second Offsets. While the First and Second Offset strategies differed in execution, both shaped the long struggle against the Soviet Union.

This article begins with the First Offset, the foundation of Eisenhower’s ‘New Look’ strategy. This strategy relied heavily on policies of massive nuclear retaliation and covert operations, but this analysis will focus primarily on the nuclear strategy component. The First Offset illustrates how the interplay of grand strategy, technology, and force design shaped America’s Cold War posture and offers lessons for today’s challenges.

Historian John Lewis Gaddis defines strategy as aligning potentially unlimited aspirations with necessarily limited means. When the scope of a given strategy becomes sufficiently large, it becomes a grand strategy.1 An offset strategy evaluates the means available to both one’s self and the adversary and recognizes a strength or capability that can negate an advantage held by the adversary. The Eisenhower administration's New Look defense strategy contained all the elements of a grand strategy and the characteristics of an offset strategy.

Ends and Means: Elements of Grand Strategy

Eisenhower came to office in 1953 determined to end the Korean War, which had been stuck in protracted negotiations. In Eisenhower’s view, the Korean war had been far too costly in American blood and treasure: a slippery slope of over-committing American forces and resources to contain the spread of global communism. Containment had been the strategy of the Truman administration, but Eisenhower believed that large, frequent, and expensive deployments of US conventional forces globally would limit the full potential of American domestic prosperity. With these beliefs in mind, and with the Korean War finally ending in the summer of 1953, Eisenhower called together a group of national security experts to design a new strategy at Project Solarium. The project included high-profile defense and foreign policy luminaries such as George Kennan and John Foster Dulles. Project Solarium provided the essential inputs for NSC 162/2 and the foundations of the New Look strategy.

Eisenhower’s strategists first determined that the Soviet Union and the potential spread of communism represented long-term existential threats, and adopted the containment of both the Soviet Union and the spread of communism globally as a desired strategic outcome. The strategy planners also identified a prosperous American economy as a second goal, while recognizing that limited means were available to achieve both ends. Any resources invested to grow military capacity to achieve foreign policy goals would necessarily limit resources available to grow the domestic economy.

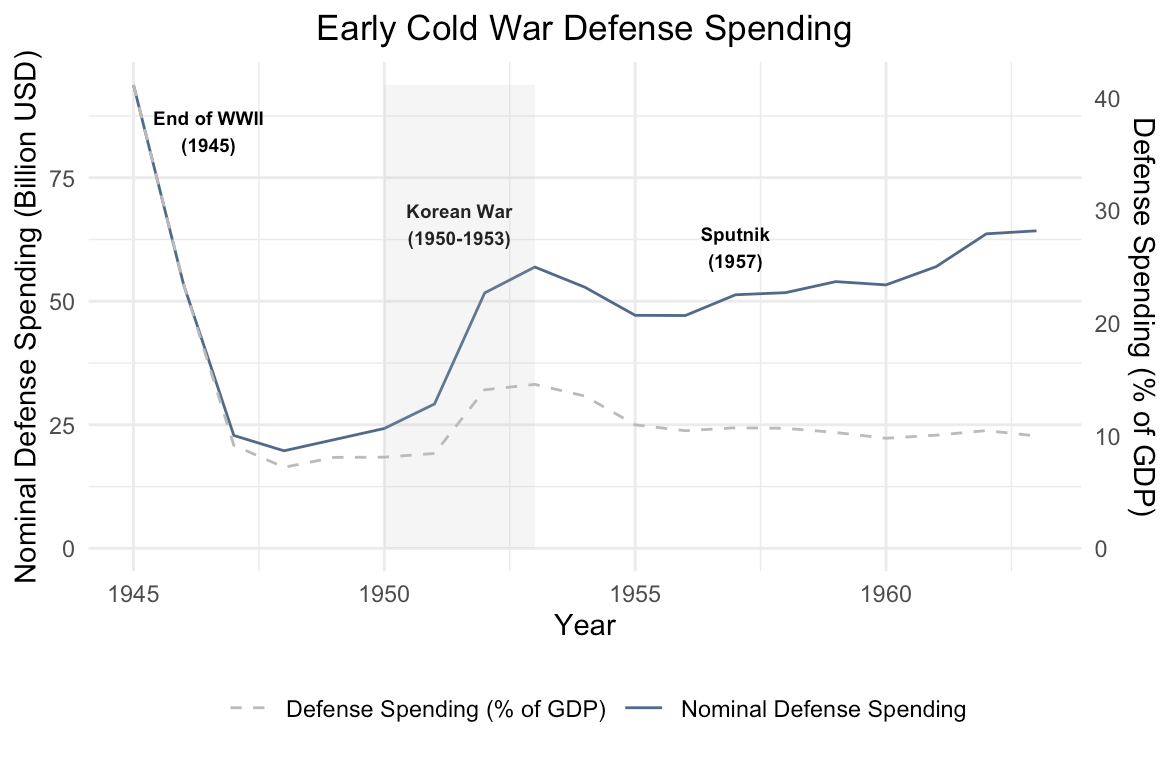

Defense spending was at historic highs during WWII, with the defense budget representing over 40% of US gross domestic product (GDP). After sharp post-war declines in defense budgets, large outlays became necessary to meet the demands of the Korean War, both in nominal terms and in defense spending as a percentage of GDP. The Korean War defense budget peaked in 1953 at $56.9 billion and 14.55 percent of GDP.2 Expenses like these drove Eisenhower’s belief that open-ended commitments to limited wars with conventional troops would slowly drain America’s economy and strength and jeopardize American domestic prosperity.

Force Posture and Nuclear Strategy

Recognizing the tension in limited means, the Eisenhower team also evaluated the resources available to the Soviets. The Soviet Union possessed a conventional mass advantage over the United States and its NATO allies. The Red Army could muster huge reserves of troops, and Soviet industry provided staggering volumes of war material. Eisenhower’s strategists assessed that the United States would be playing a losing game by trying to match conventional force levels in Europe while simultaneously responding to other Communist advances throughout the world. Instead, the administration leveraged America’s technological edge to develop an asymmetric strategy of nuclear deterrence that became known as the First Offset. By relying on superior nuclear capabilities, the US sought to neutralize the Soviet Union’s advantage in conventional forces while maintaining a more sustainable defense budget.

At this time, US military intelligence collected from U-2 spy planes indicated that the United States maintained the lead in nuclear technology and possessed the means to strike the Soviet Union. Although the Soviets also possessed nuclear weapons, they lagged behind in production and offensive strike capacity compared to Strategic Air Command. The policy of massive retaliation outlined in NSC 162/2 stated that in the event of Soviet aggression, the United States would respond with nuclear strikes (specifically tactical nuclear weapons) against Soviet military targets. American strategists believed that the mere threat of such a response would serve as a powerful deterrent, allowing the United States to maintain a smaller ground force in Europe and elsewhere.

Increasing the Nuclear Lead, Shrinking the Active Service

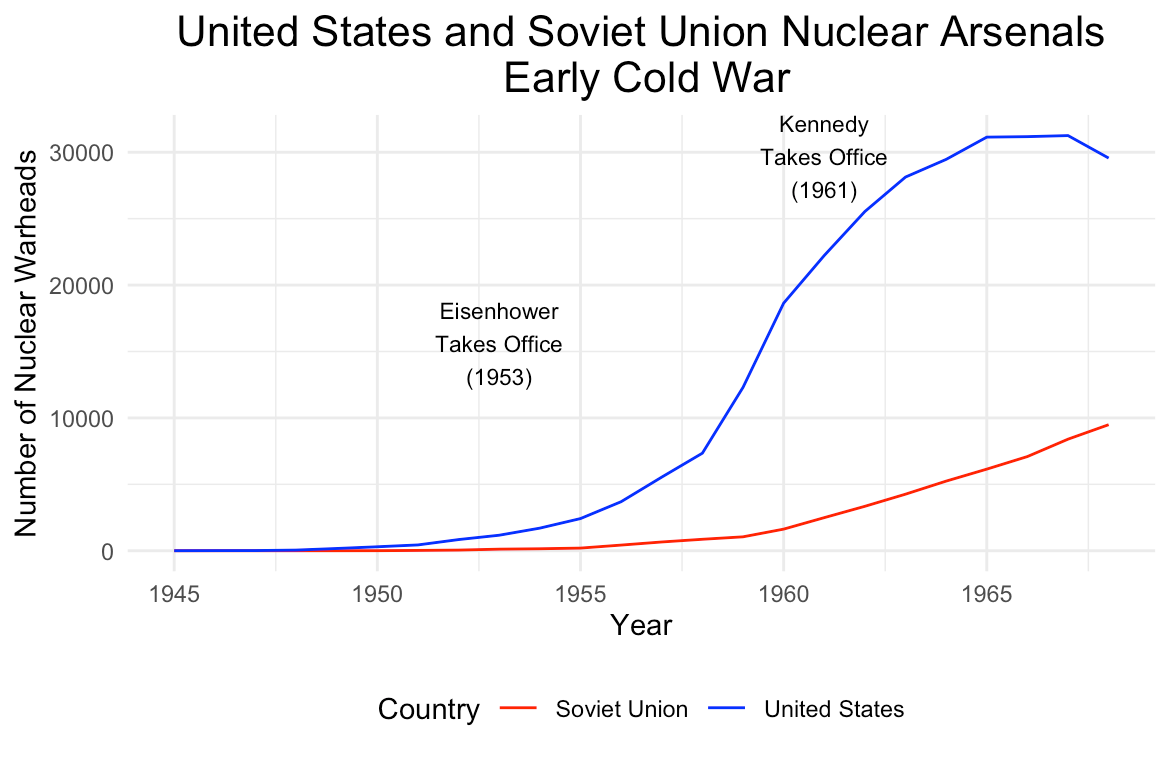

Eisenhower and his advisors correctly assessed that the United States could outproduce the Soviet Union in numbers of nuclear weapons. When Eisenhower took office, the US nuclear arsenal comprised 1,169 warheads. This arsenal would grow to 22,229 by 1961, a nineteen-fold increase. By comparison, the Soviet arsenal increased from 120 warheads in 1953 to 2,492 warheads by 19613. Thus the United States maintained a large lead in nuclear arsenal size throughout Eisenhower's administration.

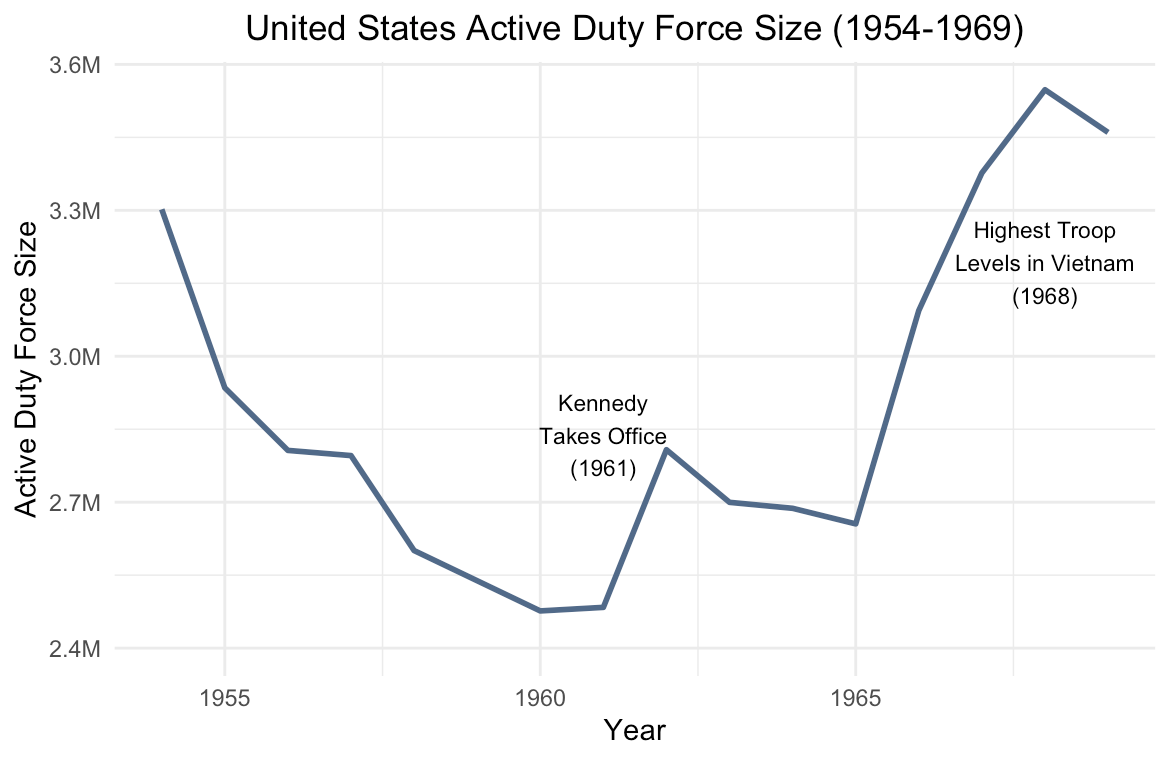

As America’s nuclear lead grew, the size of its active duty military force shrank. Data from the Department of Defense Manpower Center shows a decrease of over 825,000 active duty personnel (about 25% of the force) between 1954 and 1960. The graph below shows how the follow-on policies of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations (discussed later) led to increases in the size of the US military force following the decreases of Eisenhower's New Look.

The Central Intelligence Agency and Covert Operations

Covert operations led by the Central Intelligence Agency formed another component of the New Look strategy, providing a means to actively contain the spread of global communism without costly ground wars. Under Eisenhower, the CIA led operations in Iran, Guatemala, Vietnam, and began operations in Cuba that would lead the Bay of Pigs invasion. Through the lens of long-term historical hindsight, the results of these operations were clearly mixed. However, in the short term, these operations enabled Eisenhower to achieve multiple foreign policy goals by restoring the Shah of Iran to preserve oil interests, installing a pro-United States military dictator in Guatemala, and ensuring a separate government in South Vietnam to oppose the Communists in the North when the French departed. Moreover, these achievements came at fraction of the cost of employing conventional forces for the same ends, and avoided the domestic political ramifications of far-flung wars.

Evaluating the New Look

Many critics of the New Look and the nuclear offset strategy have emerged in the intervening years. For one, the historian John Lewis Gaddis criticized the strategy of massive response as non-credible for any threats beneath the threshold of total annihilation – meaning that the United States would not resort to nuclear weapons except in cases where its adversaries brandished truly existential threats. According to this critique, there existed a wide range of Soviet behaviors that fell beneath the threshold of nuclear employment for which the United States lacked a credible response. For example, the United States and NATO had no acceptable military means by which to halt the heavy-handed Soviet suppression of the 1956 Hungarian revolution.

A narrow focus on the nuclear offset strategy may have also led to the Eisenhower administration’s failure to anticipate the impending shift in the strategic landscape from advances in Soviet rocket and missile technology. In 1957, the Soviets put the United States on notice with a successful test of the R-7 Semyorka, the first-ever intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). American fears were further exacerbated by the launch of Sputnik later in 1957. These advances provided the Soviets with their own offset, effectively eroding America’s strategic advantage. Armed with ICBMs, the Soviet Union could carry out nuclear strikes on the American homeland, and despite the size of America’s nuclear arsenal, any use of its weapons now carried a far graver risk of retaliation.

Under Eisenhower, the United States raced to catch up to the Soviet Union's new technological capabilities. The United States launched its first satellite on January 31, 1958, followed by its first Atlas ICBM in 1959. Though the United States still maintained a numerical advantage in warheads, both sides possessed roughly equivalent strike capabilities. Thus began a tense form of nuclear brinksmanship, or what strategist, game theorist, and war quant Thomas Schelling called a game of nuclear chicken. Using the vocabulary of game theory, Schelling argued that nuclear brinkmanship did not have a dominant strategy and thus represented a very dangerous strategic situation.

These developments led the incoming Kennedy administration to criticize the Eisenhower administration for allowing a missile gap to occur4 and to adopt a strategy of Flexible Response, focused on providing options at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels rather than relying solely on massive nuclear retaliation. The strategy of Flexible Response also included a build-up of conventional forces. Of course, like its successor, this new strategy faced its own pitfalls. The Lyndon B. Johnson administration remained committed to Flexible Response and ultimately became entangled in the Vietnam War.

Despite the criticisms leveled, Eisenhower’s New Look strategy passed the most critical test of any strategy - the effective alignment of desired ends with available means, a point that Gaddis acknowledged despite his criticism. The New Look carefully balanced competing foreign and domestic goals, ensuring that economic prosperity was not consumed by strategic competition.

Eisenhower’s farewell address is best known for its warnings of the growing influence of the military-industrial complex. The speech has had many interpretations, but it should be thought of as a reminder of what defines an effective strategy — balancing ends and means.

Conclusion

Today’s strategists must leverage emerging technologies to offset adversary advantages while balancing domestic priorities and avoiding unsustainable force structures. New emerging technologies include autonomy, artificial intelligence, space capabilities, biotech, and quantum computing. Harnessing these technologies for hard power will play an outsized role in this round of great power competition – even while the world still lives under the shadow of nuclear threats. Strategists will have to identify and exploit relative advantages and remain vigilant to disruptions in the strategic landscape from new innovations. The fundamental challenge remains the same: how to deter aggression, maintain strategic flexibility, and ensure economic sustainability in an era of prolonged competition.

The views and opinions expressed on War Quants are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or any other agency or organization.

Gaddis, John Lewis. On Grand Strategy. New York, New York, Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2018.

Data on spending and GDP from usgovernmentspending.com. https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/spending_chart_1940_1963USp_26s2li111mcny_30t

Data on warheads from https://ourworldindata.org/nuclear-weapons. Data set methodology https://kyungwonsuh.weebly.com/datasets.html.

There has been a long debate and controversy about whether a missile gap in fact existed, or to what degree. Notably, rhetoric about the missile gap was part of JFK’s political rise. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/240269/pdf