Bottom Line Up Front:

Militaries worldwide are searching for counter-UAS (CUAS) solutions due to the proliferation of small unmanned aerial systems (sUAS) across modern battlefields.

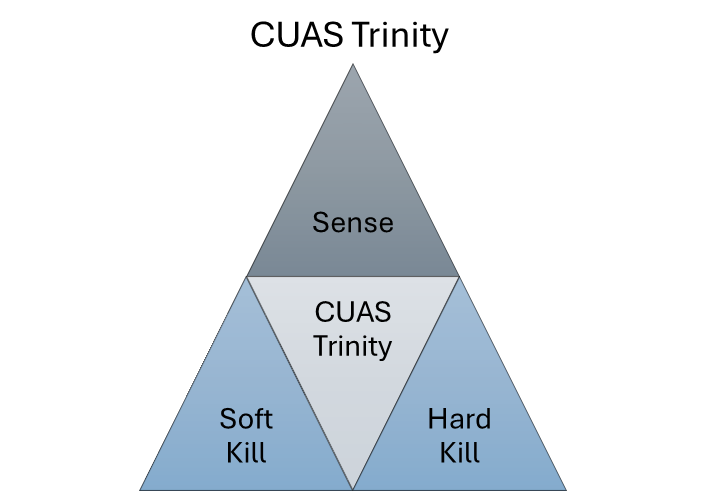

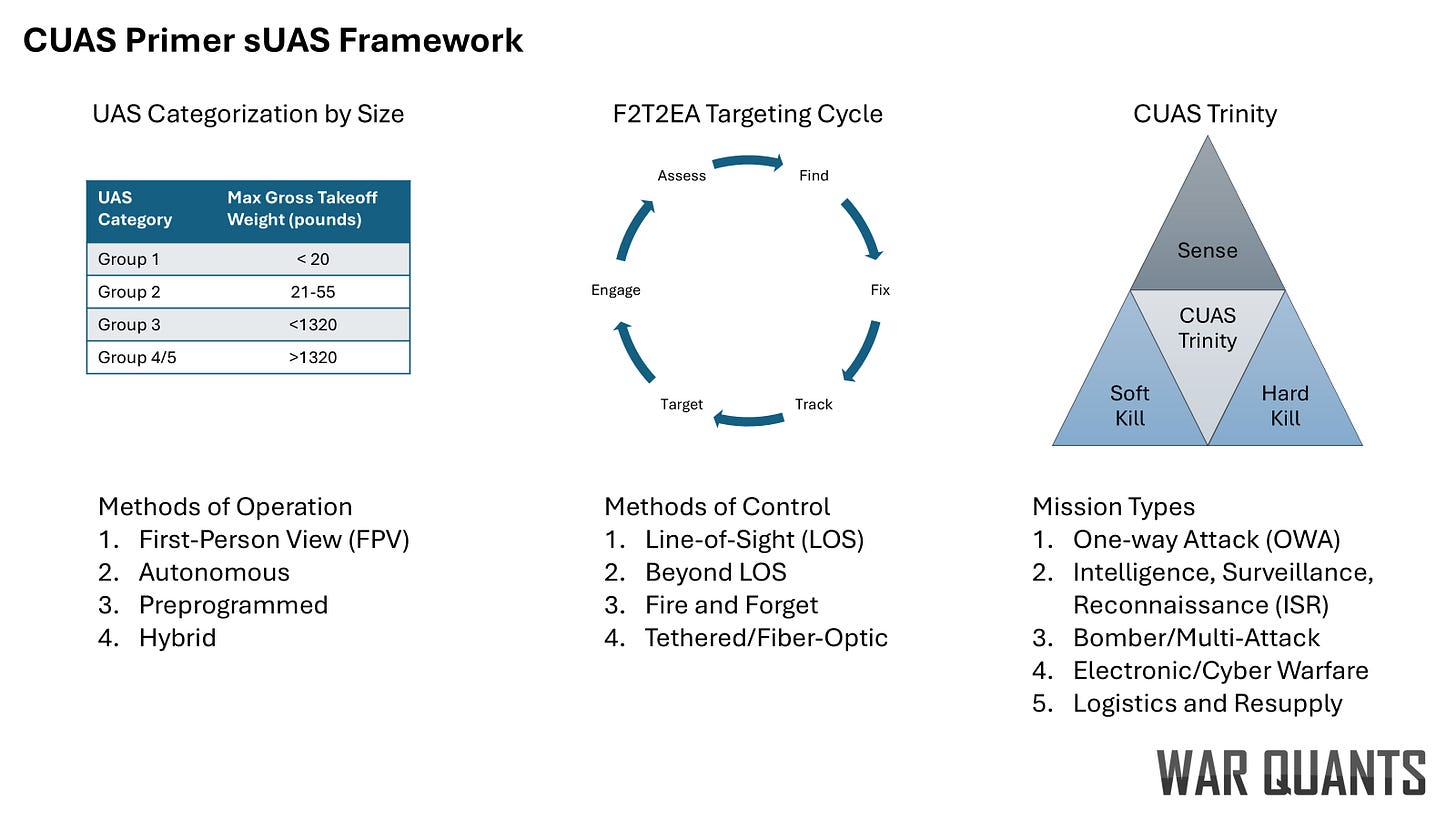

To defeat the threat, a scalable, integrated approach to using the CUAS trinity is required at the appropriate unit echelon.

The diversity of modern sUAS requires many CUAS technical solutions accompanied by new techniques, tactics, and procedures.

The modern battlefield is no longer defined by dominance in the air, but by survivability under it. CUAS falls under the larger umbrella of integrated air and missile defense, but this used to be a concern for operational commanders and staff. With the emergence of sUAS, air defense in the form of CUAS is everyone's concern, down to the lowest tactical unit. Group 1–2 small sUAS — once dismissed as hobbyist curiosities — have evolved into pervasive and lethal threats. They reconnoiter, target, jam, and kill — often at a fraction of the cost of the systems they neutralize. Evidence from recent and ongoing conflicts continues to mount: sUAS have become an indispensable feature of modern battle.

Yet despite this evidence, many Western forces continue to underinvest in CUAS systems, clinging to legacy capabilities designed for much larger threats. This decision overlooks the new economics of warfare. Cheap drones bypass expensive defenses, and adversaries have learned that volume and velocity can overwhelm even the best air and missile defense technology if it is not scaled and networked.

A new approach is needed — one that is layered, scalable, and formation-integrated. The recent Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) report, Protecting the Force from Uncrewed Aerial Systems, presents a sobering yet clear-eyed view of how sUAS are shaping the fight in Ukraine, emphasizing the urgent need for echeloned sensor-to-shooter chains and soft/hard-kill layering. Simultaneously, U.S. Army-sponsored studies conducted by RAND make the case for treating sUAS as an integral part of future formations while synchronizing both sUAS effects and CUAS defenses.

Militaries must adapt to the emerging threat posed by sUAS. This article is intended to serve as the introduction to the primer, defining key terms, concepts, and frameworks for dissecting the complex sUAS space.

Subsequent articles will be divided into sensing, soft-kill, and hard-kill sections. They will draw from those insights and add additional perspective by integrating operational modeling, kill chain analysis, and exploring layered countermeasures.

I. Understanding the Threat: Small UAS, Big Disruption

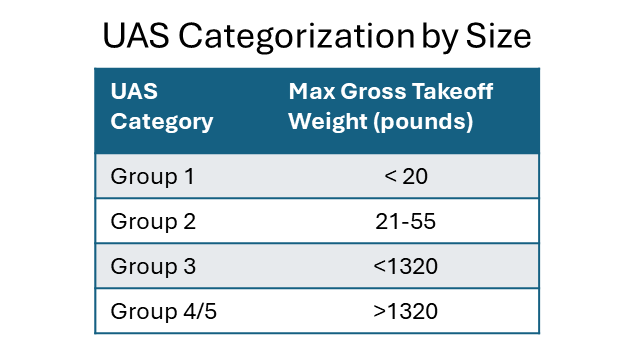

The term sUAS belies the scale of the impact of this capability on modern battlefields. sUAS have proven to be disproportionately disruptive and ubiquitous, with Group 1 and 2 platforms weighing less than 55 pounds, and available in high volumes through commercial channels either as complete solutions or modular kits. In Ukraine and in other recent conflicts, sUAS have performed critical roles in reconnaissance, fires coordination, and direct attack. Their small size, low cost, and flexible payloads allow militaries to deploy them en masse, adapt rapidly, and exploit gaps in traditional air defenses.

Taxonomy of SUAS Threats

To build a resilient CUAS strategy, we must first understand the types of sUAS in play. While each system is unique, threats fall into several general categories:

Methods of Operation:

1. First-Person View (FPV)

Often manually piloted via analog or digital video feeds, these drones are used in loitering kamikaze roles or for rapid strike missions.

FPV attack drones have become Ukraine’s signature battlefield innovation, enabling precision strikes on armor, trench systems, and command posts for as little as several hundred dollars per unit. Increasingly, semi-autonomous variants are emerging with basic object tracking or pre-programmed GPS routes, making them harder to jam.

2. Autonomous

These sUAS use onboard computer vision and decision making, AI target recognition, and other methods to find and engage targets. They can operate without a human in the loop, though rules of engagement may require human approval before they can attack.

3. Preprogrammed Route

In this case, sUAS are preprogrammed with a specific mission and a static target. They execute the mission as designed and cannot deviate.

4. Hybrid

The three methods above can be combined and employed at different mission stages or in different environments depending on operational requirements.

Methods of Control:

1. Line-of-sight communications

Often, VHF and UHF radio frequencies, line-of-sight communications limit range but are the most common in tactical operations.

2. Beyond line-of-sight communications

These drones often use satellite or communications relays. Some commercial UAS even operate on civilian cellular network infrastructure. Mesh networks allow relays of UAS and other assets to be combined, enabling an extended area of operations.

3. Fire and Forget. Autonomous and/or preprogrammed

These systems use onboard software and hardware to find, fix, and finish targets without humans in the loop. Humans can be on or in the loops; however, they are technically not necessary, but a choice of rules of engagement.

4. Tethered-fiber optic controlled sUAS

These systems physically connect the UAS to the controller. This connection cannot be jammed, but the physical connection limits their range.

sUAS Missions:

1. One-Way Attack (OWA)

OWA, or kamikaze, drones have munitions onboard and are designed to deliver their payloads by flying into the target.

2. Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR)

These drones are meant to collect information on the battlefield. Their primary payload is sensors.

Systems like the Orlan-10 perform real-time target acquisition, BDA (battle damage assessment), and artillery spotting.

ISR drones often operate persistently at medium altitude, providing fire control for precision strike systems or guiding FPVs.

Their ability to fly extended missions with minimal emissions makes them particularly hard to detect without a well-networked sensor grid.

3. sUAS Bombers/Multi-attack

Ukraine has successfully run an sUAS bomber campaign against the Russians. Colloquially known as Baba Yaga, these sUAS ideally operate for multiple missions, dropping ordnance on static and dynamic targets across the battlefield.

4. Electronic/Cyber Warfare

sUAS with EW payloads can jam, spoof, or act as decoys. A more emerging technology is sUAS, which can fly near IT networks and inject malware/cyber attacks.

5. Logistics and Resupply

Soldiers on foot and vehicles often struggle to get supplies forward on contested battlefields. sUAS can bring small amounts of high-value supplies forward at lower risk to units.

This taxonomy forms a modelable framework for sUAS classification and engagement. Take the drone below from a recent Forbes article. The article covers the recent Russian battlefield innovation of modifying drones with fiber-optic cables to allow operation in electronic warfare-saturated environments where jamming stops radio frequency control.

Using this framework, we would classify its method of operations as FPV, its method of control as fiber-optic, and its mission as a one-way attack. These three different parameters require specific countermeasures to defeat.

Characteristics That Complicate Defense

SUAS aren’t just disruptive because they’re new — they’re disruptive because they invert traditional airpower economics and defense logic.

1. Cost Asymmetry

A $500 drone can destroy a $2 million IFV or trigger the launch of a $150,000 interceptor. This cost imbalance incentivizes volume attacks and forces defenders into difficult trade-offs: overreact and exhaust resources, or underreact and take losses.

2. Size, Altitude, and Flight Profile

SUAS typically fly in the low hundreds to thousands of feet, relatively slowly compared to modern aircraft, and with potentially erratic flight paths. They can avoid radar detection by staying below the radar horizon or blending into ground clutter. Their small radar cross-section (RCS) and low thermal signature further complicate tracking.

3. Rapid Iteration and Modularity

These systems are evolving faster than most defense acquisition cycles. New drone variants appear weekly on the battlefield, often built with commercial parts, custom payloads, and open-source flight software. Modularity allows adversaries to modify drone capabilities. With a new radio or software, a drone you can jam today may be unjammable tomorrow.

II. The Targeting Cycle: How Groups of sUAS Hunt and Kill

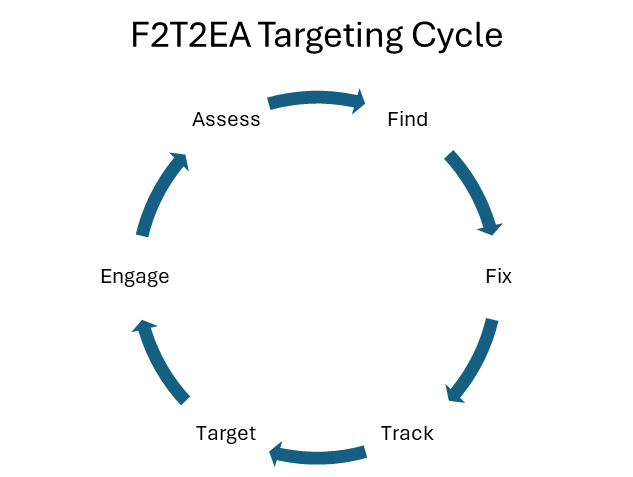

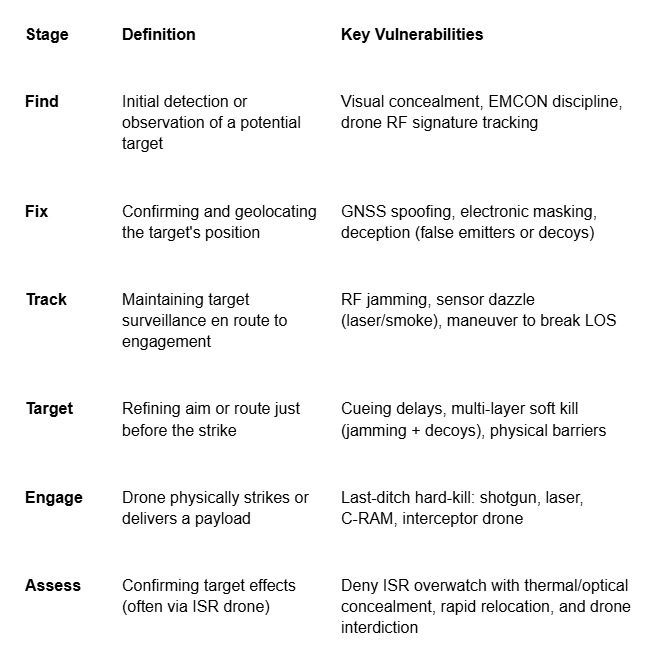

Small UAS do not operate in isolation—they form part of an evolving, decentralized kill web, executing coordinated tasks in the targeting cycle with speed and precision. This cycle, from traditional military doctrine, unfolds in six core stages: Find, Fix, Track, Target, Engage, and Assess.

In practice, this cycle is now often distributed across multiple drones. An ISR quadcopter might “find” a target, a relay drone may help “fix” its position, an FPV drone will launch to “engage,” and a secondary ISR asset confirms the “assessment.” This separation of roles enables massed, asynchronous attacks, overwhelming defenders who react only when the terminal drone is too close. Key vulnerabilities will be covered in later installments of this primer as they form the basis for defeating sUAS.

III. The Counter-UAS Trinity: Sensor – Soft Kill – Hard Kill

Effective counter-UAS defense relies on a layered approach, which we call the Counter-UAS Trinity: Sensing, Soft-Kill, and Hard-Kill. First, drones must be detected and classified using a network of sensors — radar, RF, EO/IR, and acoustic — to enable rapid cueing. Once detected, defenders may attempt a soft-kill by disrupting the drone’s control, navigation, or sensors using jamming, deception, or cyber tools. A soft-kill does not physically destroy the drone, but renders it useless. If soft-kill fails or isn’t feasible, hard-kill options — including lasers, bullets, missiles, or interceptor drones — must physically neutralize the threat before it reaches its target. Hard-kill options physically destroy the drone, rendering it unusable. Success depends not on any single layer, but on the speed, integration, and adaptability of all three working in concert.

The proliferation of sUAS demands a structured, model-driven response. This primer has defined a taxonomy for classifying threats by operation, control, and mission. The next step is to apply this taxonomy to each layer of the CUAS Trinity — sensing, soft-kill, and hard-kill — and model their performance, limitations, and integration across echelons. We can only design effective, scalable CUAS systems that keep pace with the threat through layered analysis.

Read More of Our Work Here:

Rearmament Along the Rhine

Damn the Torpedoes: Smaller, Cost Efficient, Less-than-Lethal Systems

Precision Mass at Sea: A Preliminary Analysis

Capability Analysis: AI Machine Guns for Drone Short-Range Air Defense

The views and opinions expressed on War Quants are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or any other agency or organization.

Thank you for a great primer. What struck me most was the resonance between your analysis of the sUAS battlespace and our recent work on tentative governance of non-military UAS in the UK (Lewis, de Amstalden & Paddeu, 2025). In both cases, the rapid spread of small, low-cost, drones appears to be transforming low-level airspace into a kind of common-pool resource—difficult to exclude others from, highly congestible, and subject to rapid, decentralised change. Traditional hierarchical governance arrangements, whether in civilian aviation or military air defence, seem increasingly ill-equipped to respond. Drawing on Ostrom’s design principles, we argued that drone governance now depends on more layered, collective arrangements capable of managing shared risks under conditions of uncertainty and fragmented authority.

Against that backdrop, your framing of the CUAS Trinity—sensing, soft kill, hard kill— seemed to have some fascinating parallels. It could be read as a tactical or technical framework, but also as an emergent governance model? Sensing aligns with the challenge of boundary definition and monitoring. Soft kill resembles a form of graduated sanction—disruption without destruction. Hard kill may serve as the final exclusion mechanism where softer interventions fail. What seems most significant is the interplay of these layers across units, terrains, and timescales.

It’s compelling to consider whether CUAS effectiveness might increasingly depend not just on better hardware, but on more adaptive, institutionalised forms of coordination—something much closer to a commons logic than to traditional command-and-control doctrine.