Do We Still See the Same Game Board? Schelling Points and Strategic Salience in an Age of Upheaval

The Logic of Stability

The global strategic landscape is shifting. Today’s environment is characterized by reshaped alliances, changing norms, and heightened tensions among great powers. During the Cold War, superpowers were able to navigate similar strategic shifts and ultimately avoid direct conflict, but this was no small feat, and the Cold War’s peaceful outcome was not nearly as inevitable as it now seems in retrospect. The achievement of lasting stability between Cold War competitors was a tremendous feat of statesmanship and anchored by the ideas of the world’s leading strategic thinkers. Thomas Schelling was one such strategist. As an economist and preeminent War Quant, his strategic theory was grounded in game theory. Schelling’s work helped shape the stability of the Cold War, and his major contributions included developing the related concepts of focal points and strategic salience.

This article uses game theory examples to explain focal points (now commonly referred to as Schelling Points) and strategic salience, as well as the overt and hidden factors that enable understanding and salience. These concepts illuminate the foundations of stable competition, and the lessons are of renewed importance in this new era of strategic competition. The Cold War had geographic focal points from Berlin to Cuba, alongside its broader emphasis on maintaining nuclear peace. Today’s competition has its own focal points that range from Ukraine and the broader European security architecture to the de facto independence of Taiwan, and once again, these issues must be managed amongst nuclear-armed states.

Perspective and Salience: Overt vs Hidden Differences

Strategic salience emerges when multiple actors can view the potential outcomes of a competitive or cooperative game in the same way, or at least anticipate how other actors will perceive the range of outcomes. But finding strategic salience is not always easy. In cooperative settings, the success of coordination depends not just on the structure of the game but on shared perspective. Differences in perspective—whether overt or hidden—can dramatically change what feels like the “obvious” solution.

The following examples illustrate how perspective affects or influences salience in coordination games. In the first instance, cultural context serves as an overt and commonly understood difference that can be leveraged to achieve alignment. In the second, differences in perception are hidden, even from the players themselves, making coordination far more fragile.

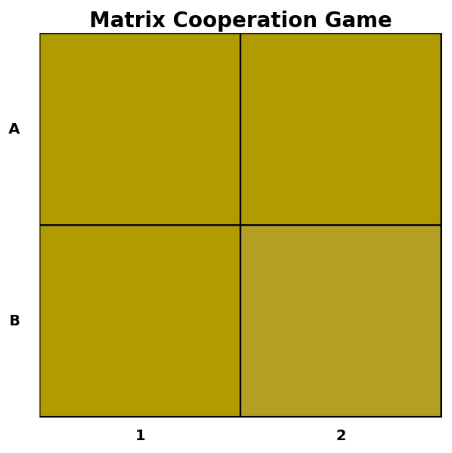

Consider a two-person cooperative game in which two players are rewarded for successful cooperation, but cannot coordinate directly. The players are separated, each given three identical balls: one blue, one red, and one white. The players are instructed to assign an order to the balls by arranging them from left to right. The players win if they arrange the balls in the same order as the other player; otherwise, they lose. A payoff matrix for this game is below:

In this game, the Nash Equilibrium is a mixed strategy, where randomly choosing one of the six orderings with an equal probability gives the players the best chance of maximizing their payout. Thus, the game is just as interesting as two players rolling a standard six-sided dice and being rewarded if the rolls produce the same result.

However, what if the players knew something about one another that gave these seemingly arbitrary colors more meaning? For example, in this game, assume both players are from the United States. In this context, these arbitrary colors go from meaningless to highly significant—these are the national colors of the United States and are always referred to in the specific order of red, white, and blue. Given this cultural context, the game shifts from the equivalent of two random dice rolls to easy money for the players.

It is essential to note that the payoff matrix has not changed—solving for optimal strategies in traditional game theory would not favor the ordering of red, white, and blue over others. Certain information (in this case, specific colors) and a shared context completely alter the game. It is this particular information and context that create the prominence of specific solutions, which Schelling referred to as a focal point in the game.

A focal point is a solution in a game that players are naturally drawn to. Schelling's most well-known example of a focal point is when he would ask students to pick a time and place to meet someone that they could not communicate with in New York City. The most common answer was Grand Central Station at noon. The location was chosen for its prominence as a meeting point, and noon was selected as the most prominent time of day. What about other games? Do all have focal points? What if you were to play this meeting game and the city was Paris, France? It is likely that most readers instantly thought of the same location. Now, what about Paris, Texas? In this case, only people who live in and are familiar with Paris, Texas are likely to converge on a prominent location; the rest of us are lacking context. Again, access to information and context is what creates prominence.

Returning to our ball game, would players find focal points in other contexts? What if the two Americans played with different colored balls, like purple, green, and brown? What if you swapped one of the Americans for a French player? Would it change the game if the players knew each other's country of origin? Does every American know the French flag is blue, white, and red? Does every Frenchman know that in America, it is red, white, and blue? Even if both players are culturally aware of the other player's perspective, the game still fails to have a single focal point. These small hypothetical examples demonstrate how small factors that are external to the game and arbitrary from a pure game-theoretic perspective nonetheless limit the level of salience.

The examples discussed above also demonstrate overt differences in perspective. In this game, knowledge about the other player's nationality and culture was critical in creating salience. What makes the differences overt is their apparent influence on the game. In most strategic games, there will be factors about the players that are overt due to their impact on the strategic actor. But overt differences don’t always have obvious implications.

A real-world example of overt factors contributing to real games of strategic cooperation and their hidden implications is apparent in the Biden Administration’s approach to Ukraine following the Russian invasion in 2022. In this instance, the Biden Administration framed the conflict between Russian and Ukraine as a fight between autocracy and democracy. Yet, given this heady framing, the administration received intense criticism for its slow and calculated delivery of specific weapons to Ukraine. This is because, despite President Biden’s rhetoric, the real focal point in the conflict was keeping the struggle below the nuclear threshold. More than once in 2022, the nuclear situation appeared tenuous, with Russia signaling its willingness to employ nuclear weapons if the United States and Europe crossed lines in intervention. This led the Biden administration to make calculated and slow decisions about weapons delivery to Ukraine, with the provision of certain high-end weapons often conditioned on adherence to acceptable use agreements. Thus, it is clear in this instance that while competing, there was simultaneously a game of cooperation surrounding conflict management, with the clear focal point being maintaining nuclear peace. This game is far more complex and dynamic than the simple ball ordering example, and the stakes are much higher.

Hidden Differences in Perspective

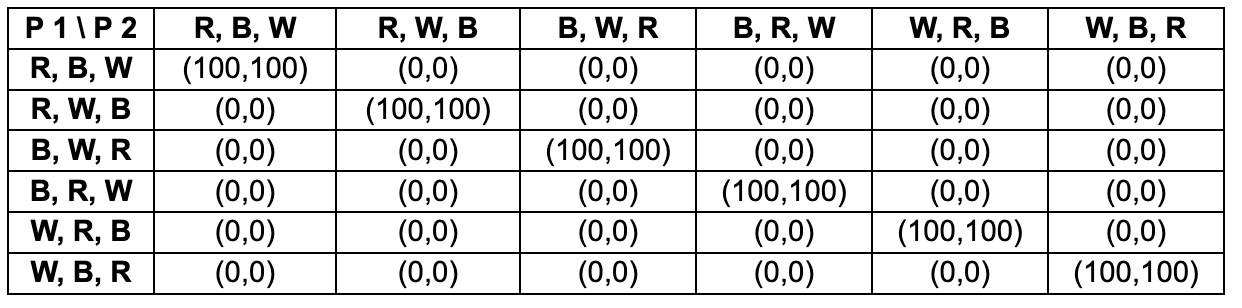

Not all differences in perspective are overt. To illustrate this, consider the following game commonly used to demonstrate focal points, but with a slight modification. Two players are once again separated and then shown the following two-by-two matrix. The players are told to choose one of the four squares in the matrix. If they choose the same square, they win. Otherwise, they lose.

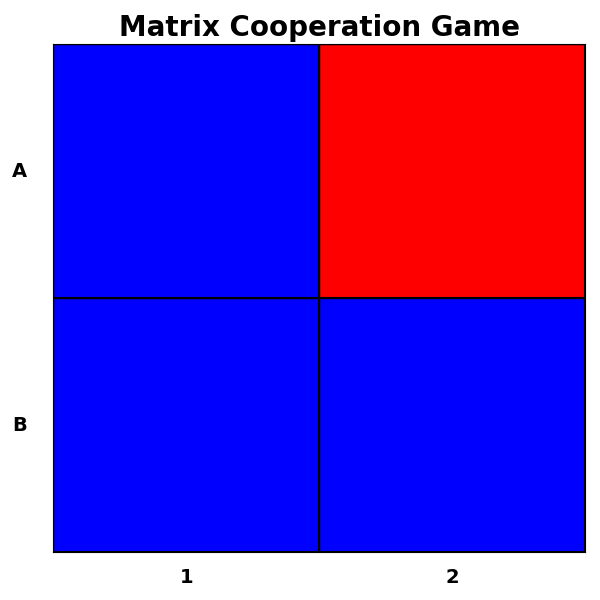

In this game, players are naturally drawn to A2 because it is the only square with a unique color. Now, consider a version of the game where the players play four rounds of the above game and are given feedback after each round on whether or not they chose the same square as the other player. However, only a mutually correct answer in the fourth round counts for a significant prize. For the first three rounds, the players are shown the above matrix, and each time, they are informed that they both selected A2—the same square. Now, for the fourth round, they are playing for keeps. In this final round, they are shown the slightly altered matrix below.

Anecdotally, consider the reaction of both players. Player 1 is initially surprised to see a different matrix, but quickly chooses B2. Player 2 is also surprised the game has been changed, and after a longer pause, selects A2. Both players are shocked to hear that they had different answers. After the game is complete, the two players can communicate. A little incensed, Player 1 confronts Player 2.“What were you thinking? We chose the off-color square for three rounds! Then you just ignored the color?”

Player 2 is confused. “In the last round, there was no difference in color for me. So I just chose the same square we had been picking. That seemed like the obvious choice to me.”

An exasperated Player 1 responds, “No color difference? Are you colorblind?”

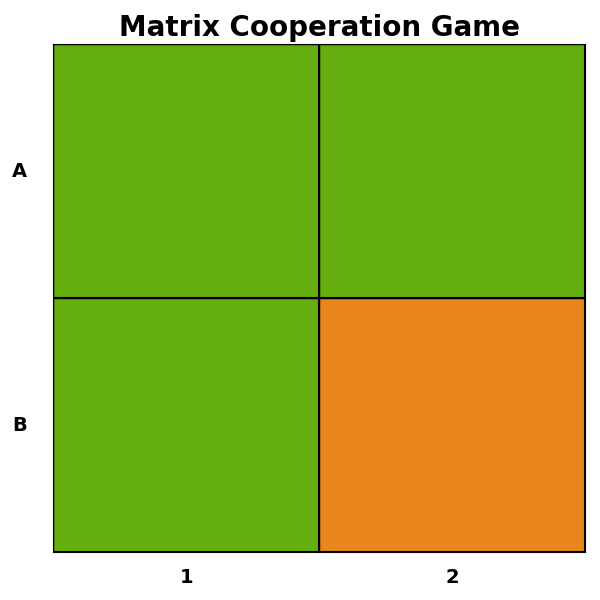

As it turns out, in this scenario, Player 2 was indeed colorblind. For people with red-green color blindness, the game matrix appears as shown in the image below.

Had player 1 also been colorblind, how might they have played the game differently? What if Player 1 understood that Player 2 was colorblind and therefore understood how they saw the board? Would Player 2’s logic of returning to past solutions have held even as color left the game?

This example illustrates several key concepts in cooperative games and their relationship to strategy. First, a common perspective is powerful and beneficial. Viewing the world similarly will naturally lead to salience in a relationship. Second, understanding the perspective of other players is important for cooperation. Without this understanding, a difference in perspective on what seems obvious may lead to misunderstanding and conflict. In this case, salience is created by strategic empathy. Last, small shifts in the game can highlight a previously hidden difference in perspective. It could be that you thought you saw the world in the same way as those you were cooperating with, but as the colorblindness example demonstrates, unknown biases can create unexpected outcomes and require players to reevaluate each others' perspectives to recreate the salience that once existed.

As a contemporary example, consider the continued divergence of perspective on U.S. involvement in European security. For decades, the United States has been an essential part of the European security architecture, and as a critical member of NATO and the primary guarantor of nuclear security for Europe, this seems unlikely to change. However, perspectives are drifting on the nature of America’s role in European security. As China has emerged as a threat to U.S. security interests, strategists and policymakers have long discussed a pivot to Asia. Initially, this shift reflected calls to end the long wars in the Middle East, but this narrative has recently expanded to include questions about the U.S. role in European security, with the depth of American aid to Ukraine in its ongoing fight with Russia emerging as an example of what is now negotiable. Just like in our matrix cooperation example, this game of cooperation has been played repeatedly for decades, and a focal point in European security has been the United States' involvement as an external balancer. But again, as in our example, the game board has changed, demonstrating that perspectives may no longer align following such shifts. Many in Europe may be angry or confused as the United States, led by the Trump administration, seems to have experienced a sudden onset of strategic colorblindness. However, the Trump administration sees Europe as having long been an enormous beneficiary of U.S. security guarantees and believes that Europe must take on more responsibility for its own security, particularly as the Indo-Pacific becomes the primary theater.

While this shift is characterized by the unique style and rhetoric of the Trump administration and domestic politics, the diverging perspectives are symptoms of structural shifts in geopolitics beyond a single U.S. administration. Significant questions remain as the old focal point of the United States as a balancing power shifts to new realities. NATO’s Article 5 will likely remain a cornerstone for balancing against Russia, but to what extent is America the underwriter of this guarantee? Will other countries like Germany step into a more prominent role? There is also no small irony in Germany stepping up as the defender of Europe, and with history as a guide, not all will be comfortable with this solution, and others, like France, see themselves playing a leading role in the emerging security order. Can the game of European security architecture settle on a new stable focal point?

Conclusion: Lessons for Today’s Strategic Competition

Since the end of World War II, international politics have been shaped by the Cold War, first through its rigid bipolarity, and then through America’s unipolar moment. As this period comes to an end, we are left with the enduring structures that the Cold War left behind. However, the world is rapidly moving on from this legacy, and actors are more willing than ever to seek advantage by discarding norms and previous assumptions that once underpinned stable competition and deterrence.

Revisionist powers like China and Russia clearly look to reshape the international system, but even the United States has now shown increasing flexibility in its interactions with the world order it predominantly shaped. The shakeup does not just apply to how rivals interact, but also how leverage and coercive power are applied to traditional allies. In this emerging world, strategic salience cannot be assumed to be present. As things evolve and the game changes, it is likely that not everyone’s perception of the problem will keep pace or be synchronized. As in our colorblindness example, today’s shifts may reveal previous blind spots in perception mismatch. Whether hidden or overt, the risk of miscalculation between both allies and rivals increases as this perception gap grows, with consequences ranging from the fracturing of an effective balancing alliance to nuclear conflict. Avoiding such perils in the short term is imperative, and in the longer term, stable competition will require the return of strategic salience.

The views and opinions expressed on War Quants are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or any other agency or organization.

Fascinating. It’s funny how many parallels between game theory/strategy and politics pop up. Nash especially, but that makes sense. Across countries, I’d imagine it’s incredibly difficult to understand other players’ perspectives due to cultural differences.